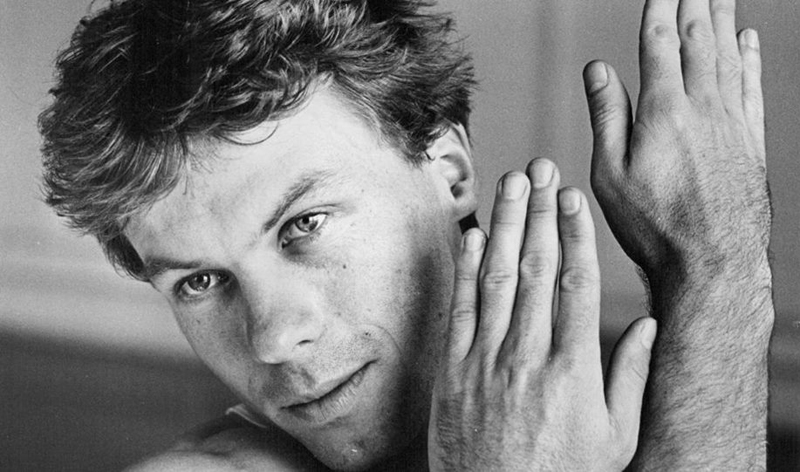

Douglas Wright, NMZM, Arts Laureate of New Zealand, 1956-2018

Written by Marianne Schultz

Kua hinga te totara it te wao hui a Tane

It is with enormous sadness that we mark the death of Douglas Wright, on November 14th, 2018. Undoubtedly one of New Zealand’s most magnificent and important artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Douglas traversed the fields of dance, literature and visual arts, making significant and unique contributions in all these forms, changing the way we move, see, think and feel. His contribution to dance in New Zealand, first as a performer, then as a choreographer and mentor, is unparalleled. His creative output, as a writer and visual artist will influence generations of people to come.

Writing in Landfall in 2001 Wright recollected, “From the earliest time I can remember, I felt compelled to move.” This need to express himself physically led to what was an accepted expression for such a child in rural 1960s New Zealand: gymnastics. Beginning with lessons at the local Pukekohe Gym, his talent was then nurtured at the Leys Institute in Auckland by coach Warren Burroughs. He was soon crowned a champion, and his place in the world of the competitive sport seemed inevitable.

However, in his late teens the appeal of drugs and alcohol replaced the thrill of medal winning. Fortunately, in 1980 Wright ventured into the Auckland dance studio of Limbs Dance Company. Attending classes in modern dance and ballet with Mary Jane O’Reilly, Kilda Northcott and Dorothea Ashbridge, Wright soon realised that dance was his calling. On reflection of this time, he recalled that he had “finally found a place I could stand in.”

Wright’s time with Limbs (1980-1983) saw him mature and grow as a dancer. With the company providing a platform, he dove into the realm of choreography. The works he made during this time—Backstreet Primary, God Bless the Child, Baby Go Boom, Walking on Thin Ice, Land of 1000 Dances, Knee Dance, Ranterstantrum—demonstrate just how hungry he was to make dances. These works, though relatively short, all possessed a unique, deep, and unsettling quality. Cath Cardiff remembers the first showing of Knee Dance in the Limbs studio; “Everyone knew there was something special happening that day.” This sentiment was echoed in Tom Brazil’s review in the Village Voice in 1984, during Limbs’s appearance in New York. Brazil stated that Knee Dance “Was one of those dances that you notice you’re breathing again when it’s over.”

In 1983, having been granted a QEII study grant, Wright set off for New York, at that time the dance capital of the world. His plan was to take some classes at various studios and return to New Zealand. An audition notice for the Paul Taylor Dance Company caught his eye. Though the notice stipulated that only male dancers of 5 feet 9 inches need apply, Wright ventured into the room with 399 other hopefuls. At the beginning of the audition Taylor came over to Wright, “You are not 5 foot 9 are you?” Douglas replied “No, but I dance 5 foot 9.” He got the job. For the next four years he travelled the world dancing in some of the most iconic works of the 20th century, learning and absorbing the craft of choreography from the master.

Critics hailed Wright’s performances with Taylor as “marvellous” and “fantastic”. While a member of the Taylor company, Wright also presented his own works in New York. In 1986 Jack Anderson, dance critic of the New York Times, in a prescient statement, described how “Wright does not merely choreograph dances, he choreographs power plays.” The following year Paul Taylor invited Wright to choreograph a new work for his company’s annual season at City Center. For this occasion Wright offered the masterly solo, Faun Variations. A huge success, the work was greeted with an outburst of cheers. Anna Kisselgoff, writing in the New York Times marvelled “The physical maneuvers in the choreography are startling… It is the remarkable resilience of the jumps, in which Mr Wright seems suspended in the air, that are the most striking.” Jennifer Dunning, also for the New York Times, referred to Faun as “one of the hits of the Paul Taylor season.” (New Zealand audiences were lucky enough to see Wright perform this work during Limbs 10th anniversary tour).

At the height of his acclaim with the Taylor company, Douglas returned home to Auckland. At the time there was talk of him assuming the helm at Limbs, but this was not to be. Instead, in 1988, he presented his first full-length work on the company, Now is the Hour. With its on-stage sheep shearing, nudity, and allegorical creatures, this work unleashed a torrent of masterpieces over the next three decades, each with its own searing, indelible imagery and breath-taking choreography and dancing. An (under) statement in the introductory programme notes for Black Milk in 2006 sums up his philosophy. “I love making things” was the explanation he gave of his output.

Beginning in 1989 with Douglas Wright and Company (later, Douglas Wright Dance), Wright embarked on creating the most astonishing dance works ever to grace New Zealand and overseas stages. For his own company; How on Earth, Gloria, Elegy, Ore, Forever, Arc, Inland, Buried Venus, Black Milk, rapt, The Kiss Inside, for the Royal New Zealand Ballet, The Decay of Lying, Rose and Fell, Halo. He also co-devised and performed in the powerful Dead Dreams of Monochrome Men by DV8 Physical Theatre in London in 1988 (on stage and in the later filmed version), eliciting the infamous headline in the Sunday Mirror, “Gay Sex Orgy on TV”. He garnered praise as Petrouchka in the 1993 RNZB production. His final choreography, M_nod, was presented in October 2018 at Tempo in Auckland. A solo danced by his long-standing friend and colleague, Sean MacDonald, the work was dedicated to his mentor and confidant, the late Sue Paterson.

Wright’s writing and visual art have been acclaimed with the publication of his two-volume ‘autobiographical fiction’ Ghost Dance and Terra Incognito, his books of poetry, and with the Auckland Art Gallery’s purchase of his most recent drawings. His artistic vision also came to life with the creation of his luscious, tropical garden, which he fashioned from a neglected section at the back of his council-owned flat in suburban Mt. Albert. The numerous dancers who worked with and for Wright together form his legacy for without their dedication, hard work and love his visions could not have been realised.

E noho rā, Douglas. With your passing the words from the conclusion of Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem are appropriate: “May angels lead you to paradise.” We in the dance community bid you farewell and send you on your way with love and gratitude for all you gave.